As Scotland’s Garden and Landscape Heritage (SGLH) Chairman I am very proud to present this story about Airth Castle by Marion Shawcross and Fiona Gordon, volunteers on the Glorious Gardens team assigned by SGLH to the recording of non-inventory designed landscapes and gardens in the Falkirk area. The Glorious Gardens project was launched in Falkirk in 2015 and was funded by Historic Environment Scotland. This is one of the 16 sites covered by SGLH in this area. A similar project was carried out in the Clyde and Avon Valley, and we are currently planning a third phase, which will focus on sites in East Lothian. For more details, please go to https://www.sglh.org.

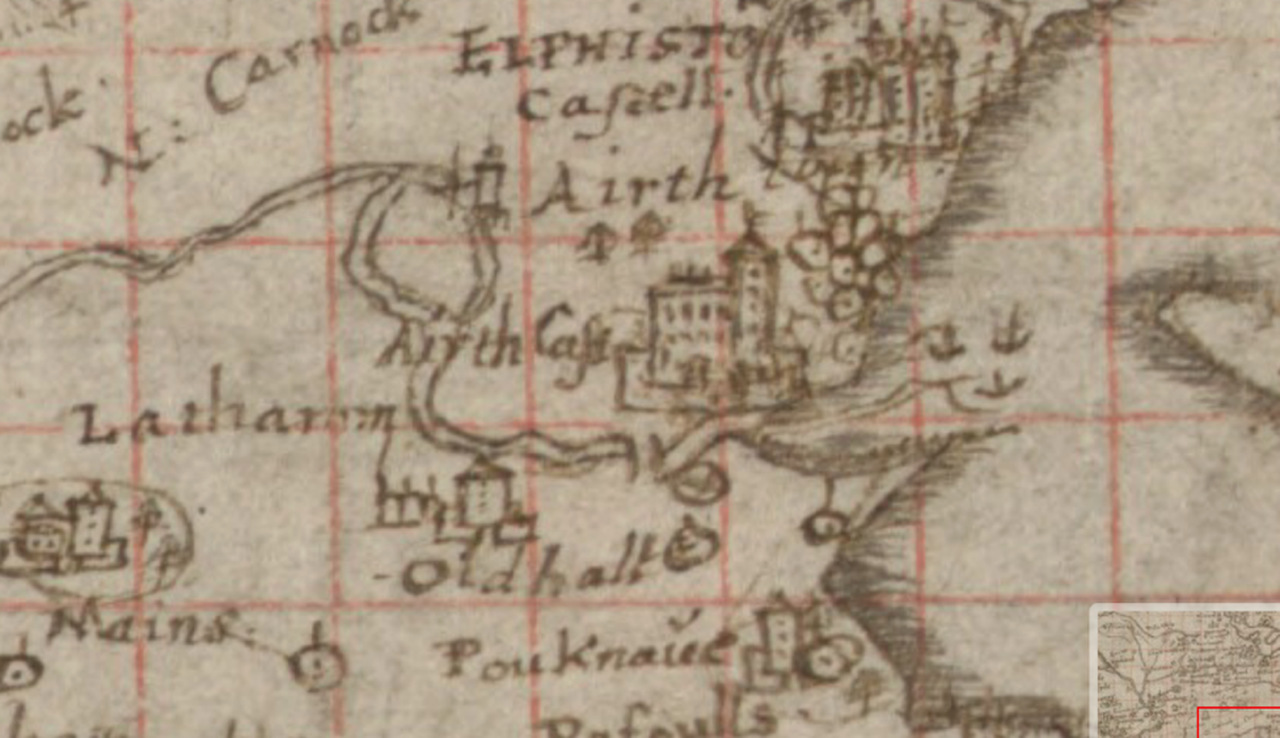

Airth Castle is an A listed castle with 14 acres of gardens and parkland, overlooking the flood plain of the River Forth. The ruins of the former parish church lie close to the east side of the castle, with the stable block to the west. It is now run as a hotel and spa but its colourful history extends back to the 13th century. In the 15th and 16th centuries Airth was a thriving town, a centre for local industry. In the early 1500s James IV designated the port a royal dockyard for the maintenance of the naval fleet. Ships were re-fitted using wood from nearby Torwood Forest. Until the river silted up around 1700, it was one of the busiest ports in Scotland.

Wallace, Bruce, Graham

The medieval tower, at the heart of the present building, known as Wallace’s Tower, is the earliest surviving structure. William Wallace was said to have rescued an uncle from imprisonment in an earlier wooden tower. In the 15th century, the Bruce family took ownership of the castle. They undertook various improvements and developed the estate resourcefully. The proximity of the old medieval church to the castle reflects its close historical association with the Bruce family. Like the castle, the ruined church and overgrown burial ground date from a number of different periods. The church is now inaccessible.

However, in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, political turmoil and the vicissitudes of family fortunes led to the castle changing hands a number of times, although ownership was largely vested in two families: the Bruces in the 16th and 17th centuries and the Grahams in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The Gardens

In 1632, Alexander Bruce, was forced into exile and had to sell Airth. He joined the Scots Brigade based in the Netherlands and married a Dutch heiress, Anna van Eyck. At the end of the 30 years’ war in 1648, they managed to retrieve Airth. Anna lived at Airth, mostly on her own, until her death in 1673. The period of her proprietorship coincided with the golden age of Dutch horticulture, and it would be hard to imagine she didn’t take an interest in the garden.

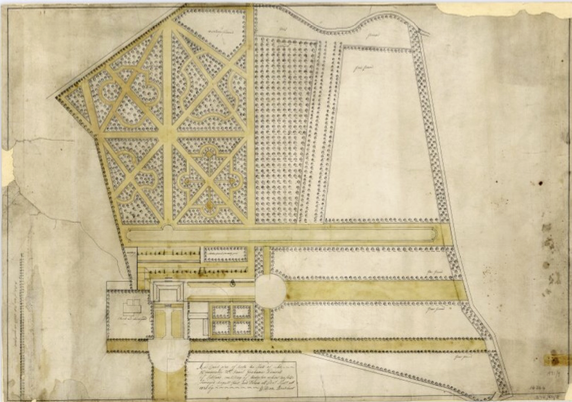

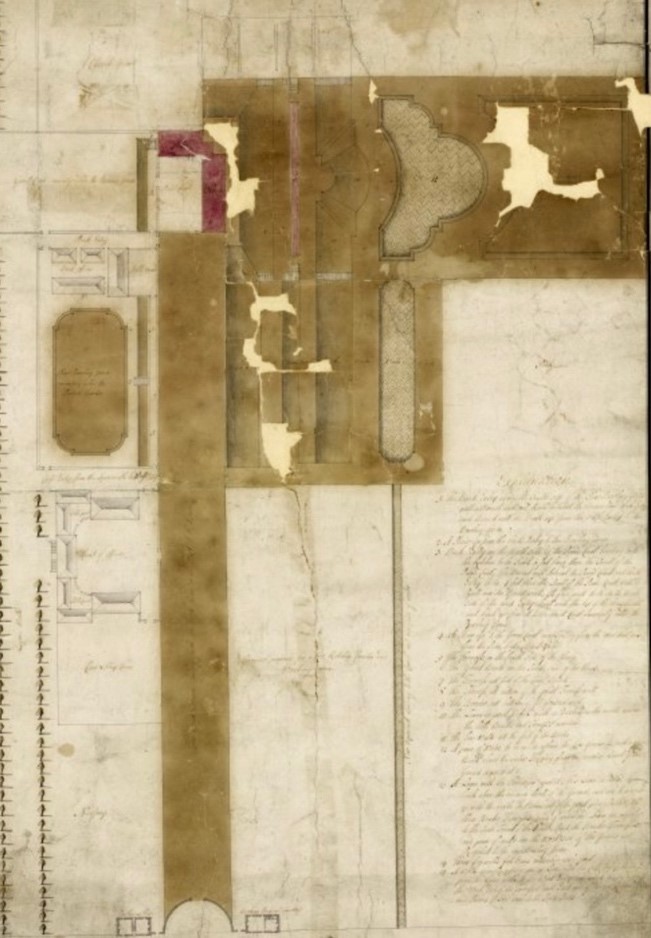

A detailed survey of the garden in 1721 by William Boutcher, a top Scottish garden designer of the time, shows some classical baroque features, the geometric framework for the relaxed parterre, avenues and canals bounded by treelined paths, and on the south side, where the ground falls away steeply, terraces optimising the local landscape.

James Graham, Judge Admiral of Scotland, had bought the castle in 1717 and sought to create a garden to reflect his status in society. He commissioned Boutcher’s survey, which was probably a proposal building on what was there. Other more detailed plans exist, possibly also by Boutcher, giving instructions for the construction of the various garden features.

Various family papers show that successive owners and their families took an active interest in the garden. In 1781, William Graham, the Judge’s son, wrote to his uncle serving in India,

“The row of walnut trees with the intermediate rowans with their blushing berries on the one hand and the larch and oaks in the quarry, and chestnut trees on the other, the stack yard where the little garden stile stands, where the rose bush still flourishes and the turf seat, though a little out of repair, might still answer the purpose for which it was intended. …… Everything would excite your emotion.”

William was a subscriber to the important 1775 book “Treatise on Forest Trees” written by William Butcher, the son of William Boutcher, the designer who had drawn up detailed plans for his father.

Extensions and Improvements

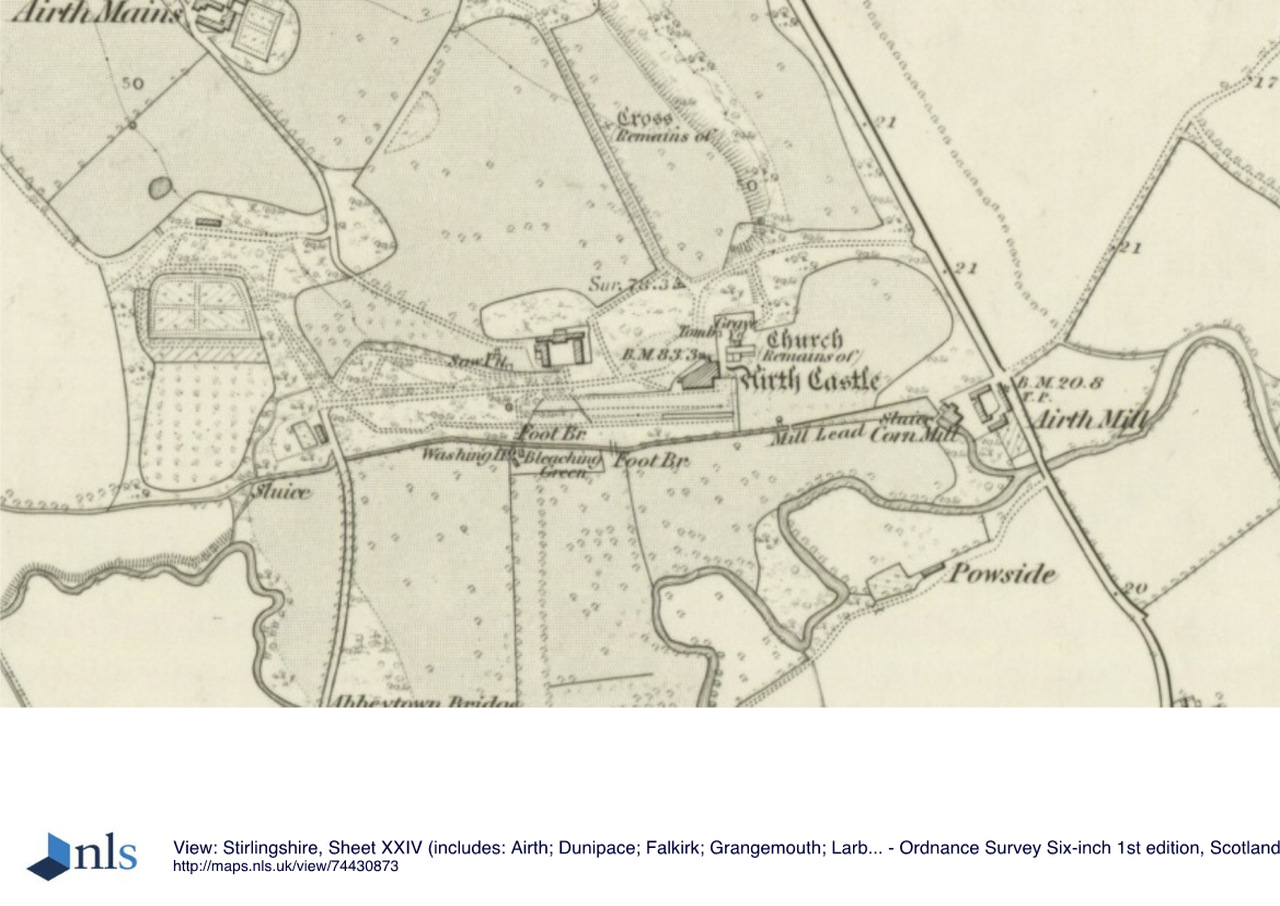

The Georgian stable block was built to the west of the Castle in 1804. Some 20th century additions, for spa and bedroom accommodation, are hidden from the main approach, screened by mature trees. Thomas Graham-Stirling, who inherited Airth in 1805, embarked on an ambitious programme of improvement, commissioning David Hamilton, the prestigious architect, to build an extension linking the two wings. His design gave the castle its distinctive castellated façade and triangular footprint. No plans for the garden from that time survive, but the first OS survey done in 1861 clearly shows terraces and avenues. William Stirling, the family architect, who implemented Hamilton’s plans, designed many buildings in the village, including Airth manse, Airth school and the new parish church. The walled garden (now containing a private house) first appears on the 1861 OS map.

Correspondence from the early 19th century shows that the family still valued the garden. In 1824, William Graham-Stirling wrote to his sister Mary:

“I think that a flower garden in the quarry on the west approach will be my ideal for the place; I think a beautiful arbour might be made there with ivy and honeysuckle and some pretty shrubs planted on the rocks in order to overshadow the arbour which make it beautiful”.

Mary’s response was not included in the bundle of letters. There is no obvious sign of the quarry today and no flower garden near the western approach where the tree canopy is now very dense. Little is known about the garden after that except that in 1877 the daughters of William Graham, the 5th laird of Airth, were writing to an uncle:

“we have taken the garden tools that papa got us in Exeter and we are going to use them to keep the garden.”

What Remains Today

Helen, the eldest, inherited the estate in 1898 but after her death in 1920 the estate was sold. It was sold again in 1971 and it became a hotel, which it remains to this day. The bones of Boutcher’s structure are still visible today, including the terraces, the approaches, some of the paths and even some of the trees. The stonework of the terraces is holding up although there are some cracks and gaps. The steps leading down to the lower terrace are overgrown and unsafe, but the views towards the Forth are notable. The bowling green and the orchards have gone and the walled garden is no longer part of the grounds, but there are still some significant trees.

In the mid-19th century, Robert Gillespie wrote that:

“In summer the avenue leading to the castle is completely overshadowed by thick foliage. But everywhere on the Airth estate are oaks, ashes, walnuts, chestnuts and elms of remarkable beauty; while across the runs of the old garden are many more specimens of the bay, Portuguese laurel and holly.” (Gillespie, 1868, page 140)

This description still captures the atmosphere of the old garden today.

By Marion Shawcross and Fiona Gordon, Scotland’s Garden and Landscape Heritage volunteers.